History

The adventurous spirit of the first great climbers to the patriotic sentiments for an Italy which had recently been united

The English Alpine Club Foundation in 1857 gives the push to assault the Alps not yet conquered. As a matter of fact, a lot of English pioneers try to reach the top of the mountain, but not only them dream the conquest. Indeed, in our valleys some “montagnard valdotain” try and dream of the peak of an inaccessible mountain. In the 1860’s for our “montagnards” is difficult, with no money and culture, to engage in an adventure so important. However, with the push given by Chanoine Carrel three men leave Valtournenche to find themselves in the Avouil mountain hut …

Conquest of the Matterhorn

Everything merges in this story: from the adventurous spirit of the first great climbers to the patriotic sentiments for an Italy which had recently been united to the analysis of the human sentiments and emotions experienced.

Though different, the protagonists of this story grew up in an environment in which Nature exerted a strong influence on their personality, making them become mountaineers driven by the desire to conquer, but respectful of the mountain.

They are men who dedicated their lives to the mountain, who developed the ability to live in harmony with Nature as beautiful as it is demanding and difficult to conquer. This is the word which recurs most often in this story, “conquest” in the broadest meaning of the term: the conquest of a peak, a goal, a deep sense of freedom.

This is the story of a man and his mountain, the story of an undertaking “that made history”.

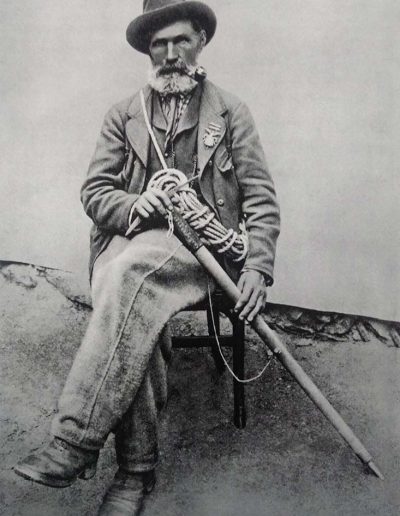

This is the story of Jean-Antoine, otherwise known as Bersagliere (Italian light infantryman).

He was born on 17th January 1829 in the village of Crétaz (a hamlet of Valtournanche, Aosta) and is considered to be the “alpine guide of Mount Cervino” par excellence.

Having returned to his valley after completing his military service, in 1857 he began his attempts to climb Mount Cervino, climbing first the Lion’s head with his Uncle Jean-Jacques Carrel and the abbot Gorret.

From then, fourteen attempts were made to climb the Italian ridge of the Lion and eight of them were led by Carrel; but from 1858 to 1863 all the attempts failed to go beyond Crête du Coq, where Carrel arrived for the first time on 29th August 1861.

The English mountaineer, Edward Whymper, had appeared in Breuil, at the foot of Mount Cervino, precisely in 1861. After choosing Carrel as his guide for the attempt of 23rd July 1862, which failed due to bad weather, he considered him his biggest antagonist, and yet admired him for his great climbing skills.

A t this point of the story, it is necessary to remember the importance of this undertaking, from a historical and civilian point of view for Italy at that time.

In 1864, in Biella, Carrel had worked with Quintino Sella – creator and founder of the Italian Alpine Club – to prepare the climb from the Italian side of Mount Cervino with the engineer Felice Giordano and with the Quintino Sella himself. Despite an unfavourable season due to bad weather, one day in 1864 Carrel advised Sella of the possibility to climb; unfortunately, neither Sella nor Giordano were available and 1864 passed without an attempt. On 11th July 1865, Carrel started to make preparations to transport the materials required on the mountain sides and on 14th July, with his compatriots Antoine César Carrel, C.E. Gorret and Jean-Joseph Maquignaz, he reached the maximum point of the preceding climbs, but it was too late to complete the climb and reach the summit. The roped party decided to stop at a lower point to rest.

An historical document recalls the attempt of 14th July 1865. In a room at Hotel Giomein, the engineer Felice Giordano [one of the founders of CAI] writes to the Minister of Finance Quintino Sella:

“Dear Quintino, I am sending you an express telegram to St. Vincent, seven hours away from here on foot; for safety reasons I am also sending you this. Today, at 2 pm, with the use of a good pair of binoculars I saw Carrel and his party on the extreme peak of Cervino; others with me also saw them; success seems certain despite the recent bad weather which has covered the mountain with snow. Set out immediately, if you can, or telegraph me at St. Vincent. How strange, I don’t even know if you are in Turin! I have had no news of this person for eight days; I am writing by chance. If you don’t come, or telegraph me by tomorrow, I will climb to plant our flag, the first”.

However, as Giordano was writing these joyful words, on 14th July 1865 seven mountaineers appeared on the summit: Edward Whymper – who had decided to climb Mount Cervino from the Swiss ridge of Hörnli – with the guides Michel Croz, Peter Taugwalder and his son, the occasional companions, Charles Hudson, Lord Francis Douglas and Mr. Hadow, who were all English. On the way back, the rope party suffered a serious and tragic accident from which only Whymper and the two Taugwalders survived. The tragic event, followed by a trial which attributed the tragedy to a faulty rope, caused a sensation in the mountaineering world and beyond, leaving a life-long mark in the mountaineer’s conscience.

On 15th July, at the same table of Hotel Giomein, Giordano was forced to correct himself and sadly wrote to Sella:

“Dear Quintino yesterday was a bad day and Whymper ended up beating the unhappy Carrel to the peak”.

Having returned to Breuil, encouraged by Giordano and the abbot Gorret, the Italians formed a climbing party composed of Carrel, Jean-Batptise Bich, known as Bardolet, Amé Gorret and Agostino Meynet. They departed again on 16th July, and after having camped at Gran Torre the next day they quickly reached the base of the Head of Mount Cervino finding a way on the northern slope; having stopped to facilitate the return of Carrel and Bich, Gorret and Meynet quickly reached the peak. Within a few days, the peak of Mount Cervino, the last 4,000 metre mountain in the Alps left to climb, had been finally reached by the two sides.

After his conquest of Mount Cervino, Carrel dedicated much of his life to enhancing the Italian route up the mountain. In 1867 he took on the task of building the refuge at “Cravate” (4,114 metres), at a cost of 585.50 lire, a sum gathered with a subscription among Italian and foreign mountaineers and personalities from the Aosta Valley; Carrel himself gave 10 lire, as did many guides from Valtournanche!

On 26th August 1890, while returning from the Mount Cervino refuge, with the mountaineer Leone Sinigaglia and the guide Carlo Gorret, a short distance below Lion’s col, at an altitude of 2,915 m, after having led his rope party for 16 hours in the midst of a raging snow-storm, Carrel suffered a heart attack and died.

Carrel Point (between the Lion’s Head and Dent d’Hérens, Pennine Alps), the refuge hut on the Italian Matterhon ridge and the cross where he died are named in his honour.

Luigi Amedeo di Savoia’s hut

Custom made in Turin by C.A.I, has been strip down and carried to the foot of the Matterhorn in 1893 where has been reassembled at 3840 mt on the Cresta del Leone (named the Italian way), the mountain hut has been dedicated to Prince Luigi Amedeo di Savoia Duca degli Abruzzi for his several climbing expeditions.

Given by Club Alpino Italiano ( C.A.I.) to Società Guide del Cervino in 1995, the Lodge became a mountain hut for the history of mountaineering. In 1968 a new and bigger mountain hut Jean-Antoine Carrel has been built and took over 10 meters below.

Built on wooden boards, the main façade highlights, based on the board irregularity, as of the mountain hut has been founded and adapted to the rocky ground and its trace is evident also on the wood below the metal sheet coverage. The sides covered in metal sheet were positioned north and east for clear reason of thermic isolation due to the lack of sun exposure. The windows originally based on the south and west façade have small dimensions in order to benefit from the minor heat loss possible.

The mountain hut had 10 sleeping area on two large wooden boards covered by horsehair mattress. Inside, totally built in wood, it was heated by a small stove with its external chimney facing down in order not to be blocked by the snow. 2003 landslides on the Matterhorn have almost compromised the integrity of the hut and in order to preserve its indemnity and constitute a memorial, the Società Guide del Cervino has taken it down.

Strip it off on site during summer 2004 has been transported to the bottom of the valley, rebuilt and placed in front of the office of Guide del Cervino to become a museum of mountaineering history and protagonist of memories to all who have visited and lived with.